In this post we’re going to be discussing N+1 queries - what they are, why they’re bad, and how this relates to ActiveRecord and Rails.

What makes queries slow

The first thing to remember when dealing with accessing a database is that, generally speaking, it’s the number of queries that slow you down, not the size of the individual queries. This means that if we do a single SQL query to retrieve 10 users, another SQL query that retrieves 100 users wouldn’t actually take much longer, assuming it was still a single query, same as the first. There are of course exceptions to this, but it’s a good rule of thumb, and it’s something we’ll want to remember going forward.

A quick note, I’ll be using the word query a lot in this post. I’ll be talking about both ActiveRecord queries and SQL queries. An ActiveRecord query generates a lot of SQL queries, so when I describe an ActiveRecord query as “large,” I generally mean that it generates, or is made up of, many SQL queries.

Rails example

To explore this idea a bit further, let’s take a look at a Rails example. Let’s say that we have a User model, and that users have a name and age, and are associated with a Car object, which has a mileage attribute.

Let’s then suppose that we have a users index page where we want to iterate through all users and print out their name, age, and the make of their car. Our erb file might look something like this:

<% @users = User.all %>

<% @users.each do |user| %>

<p>Name: <%= user.name %></p>

<p>Age: <%= user.age %></p>

<p>Car Mileage: <%= user.car.mileage %></p>

<% end %>Pretty simple. Now let’s go ahead and take a look at the actual database queries that are taking place here.

We start by grabbing all of our users. Under the hood, that’s a single, simple SQL query. SELECT * from users. Depending on the number of users we have, that could be a pretty big query, but it’s never going to get too crazy, since we’re still only doing one. Once we’ve gone ahead and completed that query, we now have all of our users stored in primary memory in the variable @users, and we can essentially do anything we want with them. So when we go to display their names, no problem! When we go to display their ages, easy peasy. It’s all loaded into memory already, it’s no issue.

What N+1 means

However, things start getting tricky when we go to render info about a user’s car. When we do user.car in the snippet above, we are not accessing an attribute - we are accessing an association, and by extension, an entirely different table. So to access the car object for a given user, we have to do a brand-new database query. So as we’re iterating through our user objects, we end up making an extra database query for every single one of them, to access its associated Car object. If we have 50 users total, that “Car Mileage” line is responsible for increasing the total number queries from 1 to 51.

This is what N + 1 means. “N” is the total number of rows in the original table, and “1” refers to the “original” number of queries that we are making against that table before we got screwed up by accessing associated tables as well.

Why I think the term “1+N” is better

In my opinion, the previous paragraph is a bit confusing, and I think it can be improved if we use “1 + N” instead. In English we read from left to right, so it makes sense to set things up so that the leftmost value in the expression equates to the first part of our query. Let’s try again.

In a 1 + N query, “1” refers to the original number of queries we made. When we did User.all, that only generated a single database call, and we got back a bunch of rows from it. Awesome. However, when we start grabbing associated rows in another table for every one of our original rows, the size of the query starts to grow rapidly. In fact, for every user that is added to our database, that particular page is going to need to do one more query. The number of additional queries we end up doing, which is the same as the number of rows returned by the first query we did, is called “N.”

This situation is what is called 1 + N. It is also known as linear growth. The amount of compute time goes up linearly with the number of records returned by your first query. Now at first that might now seems too bad - it might even seem to make sense. You’re retrieving one more user than normal, why shouldn’t the time for the query increase? But remember what we touched on at the beginning of the post - additional rows do not significantly increase query time, only additional queries do. So it’s absolutely possible to massively scale the size of our database while still keeping our ActiveRecord queries fast, by simply making sure that they produce as few individual SQL queries as possible.

A quick review of .joins and .includes, and mitigating 1 + N queries

Before we go any further, let’s take a second to review the .joins and .includes methods that ActiveRecord gives us.

.joins can be called on a ruby class, or ActiveRecord relation, and takes as an argument a symbol representing another table. It does what it sounds like - it generates some SQL that creates an inner join on the second table. The thing to understand about .joins is that it works on the SQL side - it specifies what happens during the course of the SQL query, not after the query, when things are loaded into primary memory.

It’s nice for when you want to have fine-grained control over how your ActiveRecord executes some query or another, but it doesn’t solve the problem that we’re dealing with here, of having to do several SQL queries to get our job done.

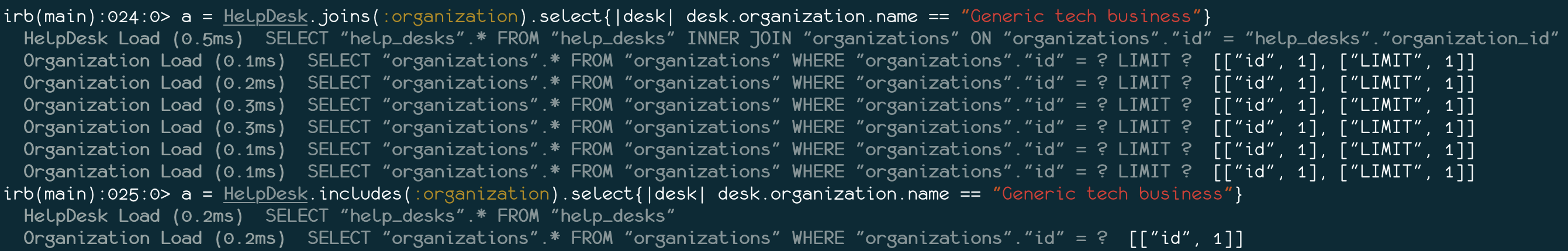

.includes is a rather different animal from .joins. Instead of doing a join in the SQL, it just looks at all of the rows in the first table that have a foreign key value pointing at row in the second table, grabs those rows from the second table, and loads them into primary memory so that they can be used whenever we like in our Rails code without necessitating a second query. I hopped into my most recent project, HelpZone, recently, to provide an example. A HelpDesk belongs_to an organization. Take a look at the difference in number of queries between one and the other:

As you can see, in one of these scenarios we end up with a “1 + N” query, which will grow slower and slower over time as the number of rows in the help_desks table grows. In the other scenario we only have two queries, and we’ll only ever need two queries, no matter how large the table grows. Beautiful.

A brief mention of Big O notation

One thing we should touch on before we go is Big O notation. Big O notation is a way of expressing how the time to complete a query will grow as we add more and more table rows into the mix. Sound familiar? The O simply stands for Order of Complexity - it’s not a function or variable or anything like that - this is just a way of notating different ways in which query execution time can grow in response to additional rows. Here are some examples:

O(1) : This notation indicates a query that will always take the same amount of time to execute, no matter how many rows we’re dealing with. This rarely shows up in real life, but boy would it be nice.

O(n) : This notation indicates a query where the amount of time to execute goes up in direct proportion to the number of rows that we feed into it. This should sound ver familiar - it’s our “1 + N” query! It’s linear!

O(log (n)) : This is where things get a teeny bit out of my depth… but I’m pretty sure that this is notating a situation where each additional row slows the query down, but by a smaller amount than each previous row. I think that this is what we get when we do User.all. Either way, I’m pretty sure that having your queries scale like this is a really good thing.

O(n^2) : We’ve looked at the best, so now let’s look at the worst. A query with this notation will have its time to load increase exponentially as the number of rows increases. So if you were grabbing all users, each additional row would take twice as long as the one before it. Needless to say, this is a nightmare situation, and it makes linear time look friendly by comparison.

Wrapping up

When I read stuff about N + 1 online, it’s clear to me that the concept is a fuzzy one for a lot of people. If you remember one thing from this post, let it be this: the “N” in “N + 1” refers to the number of rows in the first table you queried. If you remember that, you can piece everything else together just by thinking about it for a bit. To explore this topic a bit further, I recommend checking out some of the links below. Also, hop into rails console and play around with different ActiveRecord queries, paying attention to the SQL that is generated, and the subsequent execution times. Thanks for reading!

Further reading

Contains some great information about Big O notation and query execution times in general:

Estimating Time Complexity of Your Query Plan

Introduces bullet, a gem that warns you about N+1 queries in your application:

The Silver Bullet to the N + 1 Problem